Aligning the World: A Brief History of Cartography

A map never shows the world as it truly is. Every line, every center, and every blank space reveals how people have interpreted their surroundings. Cartography does not merely indicate where places are located; it also exposes who was looking, why, and for what purpose. Its history is therefore a history of power, knowledge, and imagination.

The First Maps: Orienting to Survive

Long before the existence of countries or continents, people were already mapping their immediate environment. The oldest known maps date back to Mesopotamia (around 2500 BCE) and were carved into clay tablets. They depicted rivers, fields, and settlements; essential elements for trade, irrigation, and survival. These maps were not “accurate” in the modern sense, but functional. They were less concerned with scale or distance than with meaning.

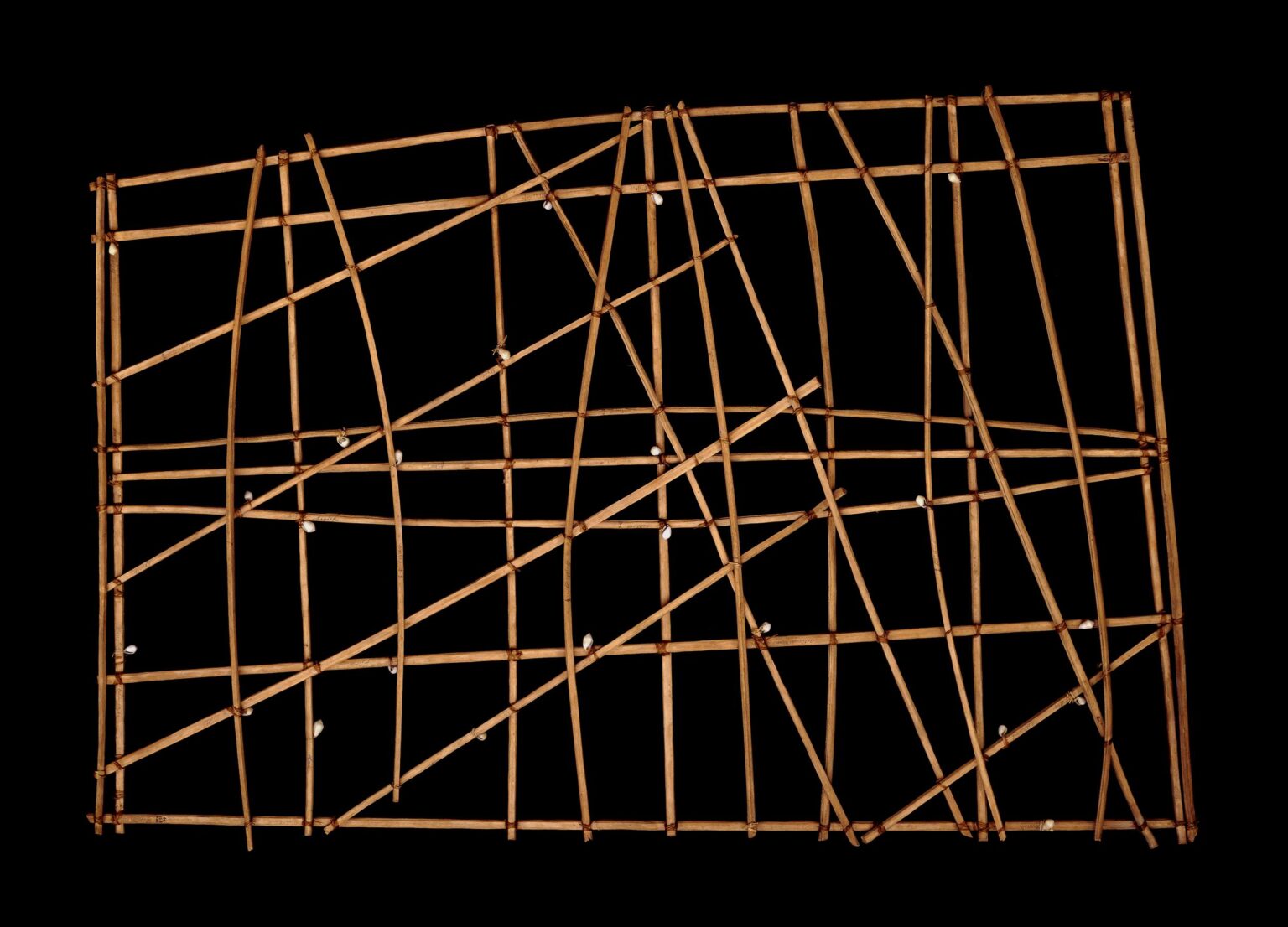

Other cultures developed their own cartographic traditions. In China, maps were used early on for administration and military strategy, while Polynesian navigators crossed vast ocean distances using stick-and-shell charts—maps read not only with the eyes, but through experience.

Classical Antiquity: Measuring the World

The Greeks introduced a revolution by applying mathematics and astronomy to cartography. For the first time, the world was approached as something measurable. In the third century BCE,Eratosthenes calculated the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy. Centuries later, Claudius Ptolemy compiled geographical knowledge in his Geography, introducing coordinate systems that assigned fixed positions to places. This idea would form the foundation of all later mapmaking.

The Middle Ages: Maps as Worldviews

Medieval maps, such as the famous mappae mundi, were less concerned with navigation than with symbolism. Jerusalem often occupied the center, with east placed at the top. These maps did not tell a story of distance, but of faith, power, and morality. They reveal how deeply cartography is shaped by culture and historical context.

At the same time, cartography flourished in the Islamic world. Scholars such as Al-Idrisi combined the knowledge of merchants and travelers into remarkably accurate world maps that would remain influential for centuries.

The Age of Discovery: Maps as Power

From the fifteenth century onward, everything changed. European seafarers ventured across the globe, and maps became strategic instruments. Portolan charts, with their detailed coastlines and networks of compass lines, enabled long sea voyages. In 1569, Gérard Mercator introduced his famous projection, allowing sailors to navigate on a constant bearing—a breakthrough for navigation, though one that introduced distortions still debated today.

Maps defined borders, legitimized claims, and laid the groundwork for colonial expansion. Those who drew the maps often controlled the narrative.

From Paper to Pixels

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, cartography became increasingly scientific. Elevation measurements, aerial photography, and later satellite imagery brought unprecedented accuracy. Today, we live in an era of digital maps, GPS, and geographic information systems. With a single tap on a screen, we know where we are, and where we are going.

Cartography is constantly evolving, yet it never disappears. Each era draws the world as it understands it: through myths, measuring instruments, or satellites. Maps therefore reveal not only where we are, but how we see. And as long as people continue to travel out of necessity or curiosity, they will continue to redraw the world.a Terre.

Opening Hours

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

10:00 - 18:00

Closed

Visit our travel bookshop

Anticyclone des Açores

Bondgenotenlaan 104

3000 Leuven

call+32 (0)2 217 52 46anticyclone@craenen.be Contact us

Visit our travel bookshop

Anticyclone des Açores

Bondgenotenlaan 104

3000 Leuven

call+32 (0)2 217 52 46anticyclone@craenen.be Contact us

Opening Hours

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

11:00 - 18:00

10:00 - 18:00

Closed